Who cares about the world? On the power of responsibility

- Dossier

- Oct 22

- 20 mins

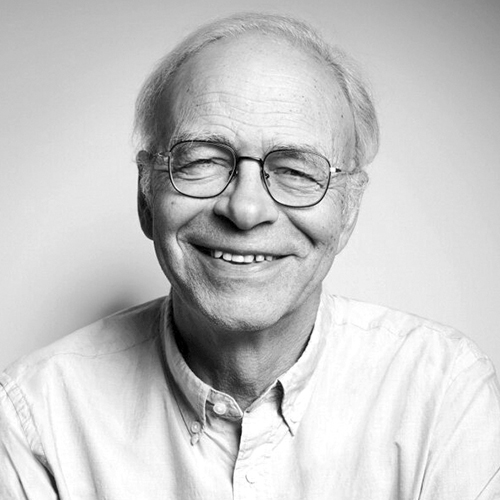

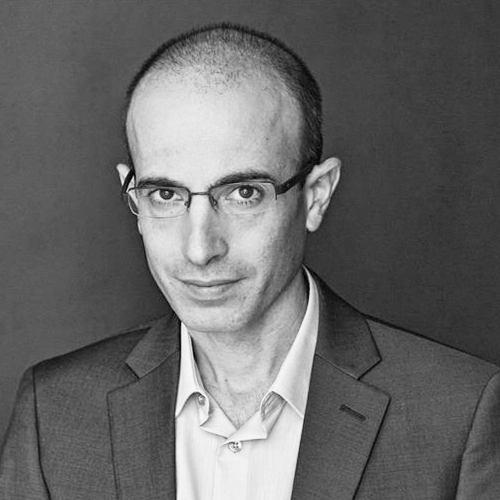

Singer and Harari discuss how individual responsibility towards others and the planet should be exercised. To accomplish collective goals such as the fight against poverty or animal cruelty, they believe that institutions in which citizens can trust are key. Committing oneself to a cause and seeing how results are achieved gives life a sense of purpose.

Peter Singer and Yuval Noah Harari were guests at the 10th edition of the Mishkenot Sha’ananim Jerusalem Writers Festival, where they took part in a conversation led by neuroscientist Liad Mudrik under the title What did you do today for planet earth? This event was part of the ‘On the Power of Responsibility’ series, which was organised in collaboration with the Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung Foundation of Israel. This article covers the conversation between Singer and Harari, facilitated by Dr. Liad Mudrik.

Liad Mudrik: In the modern age, we face issues of responsibility to humanity as a whole, as well as to other animals that inhabit the planet, and even the planet itself. What are the limits of our individual and collective responsibilities?

Peter Singer: We are responsible for everything that we could do to help other sentient beings, whether human or non-human, whether they are living now or will live in centuries to come. The limits to our responsibility? Firstly, our ability to change things, and to change things for the better, which is obviously what we should be doing. And the limits of our knowledge, which may mean that we don’t know how certain interventions will pan out; that’s particularly relevant when we’re talking about the future. But it may also be relevant to some extent when we’re talking about people who are part of a different culture in another country. So, it’s really important to inform yourself and know that you are actually going to help in the way that the people you’re trying to help want to be helped.

Yuval Noah Harari: I completely agree. I think that our responsibility extends as far as our power extends, and one of the problems we face is this mismatch between our power and our knowledge; over thousands of years the power of human beings has increased enormously but our knowledge is not catching up. It’s much easier to build a dam over a river than to understand the full consequences – to know the full consequences – for the fish, for the birds, for the trees, for the climate, for us. And it’s even doubly true on an individual level. Now I’m connected through causal chains to everything that’s happening around the world. But to investigate even one simple thing, like, where does this shirt come from? And which humans or animals may have suffered in the production of this shirt? It would take me literally years to really know the full consequences of buying this shirt.

Singer: There are clearly also limits to how much we can care for all of these different things. We all have our priorities and there are certain things that I’ve tried to do relating to the treatment of animals and the consequences of eating them. Things relating to what we can do to help people in extreme poverty through donating to effective charities, but there simply isn’t time to inform myself properly about every consumer item that I might wear or buy or use in some way.

Harari: That’s really quite a novel problem in history, because if we go back to the Stone Age, the type of life that people, humans, lived for most of their evolution, didn’t involve these kinds of ethical questions. As a hunter-gatherer you know most of the consequences of what you do, because it’s very local. It’s very rare that you do something which has a significant impact on a distant place or on unfamiliar people and animals. So, in a way, from an evolutionary perspective, maybe our ethical sense or ethical instincts did not evolve to deal with the type of ethical questions that we are now facing in the 21st century.

Singer: Although, you’ve pointed out that our ancestors or the indigenous peoples didn’t always know the consequences of what they were doing either. I’m speaking to you from Australia. When humans came to Australia, they wiped out something like 90% of the large mammals in the country. I’m sure they didn’t know that by the number that they were killing, they were going to leave fewer animals to hunt for their ancestors. But it happened, nevertheless.

Harari: That’s absolutely true. Of course, it happened over thousands of generations. I think that the main difference is that they really were not in a position to understand the long-term consequences of what they were doing. At least collectively, we are in a position to do it. We have the ability to understand what we are doing to the planet, to the climate, to other animals. It’s just that to do it, we need to rely on collective institutions that gather the knowledge and analyse it, and so forth. Ethically, we tend to rely on ourselves, but to deal with problems of this magnitude, we basically need to rely on these huge institutions, which feels alienated. This is part of the reason for the deep ethical crisis we’re facing.

“For the first time in history, hunger and disease are no longer uncontrollable forces of nature. Unfortunately, we do not always have the good sense or the compassion to use the resources available to us”. (Yuval Noah Harari)

Tackling poverty

Mudrik: On the other hand, our ethical reflexes, if you like, have also expanded. Today, I get information about human suffering that is not related to my wellbeing here and I developed this empathy muscle I can relate to that. So maybe modernity also led to an expansion of our moral responsibility, of our empathy.

Singer: Yes... I think our understanding of the world as a whole has extended our empathy to some degree, obviously still to a far too limited degree. We’re still not doing nearly enough to help people in extreme poverty. We had another example of that just now during the Covid crisis, in that in the affluent countries, everybody got two vaccines if they wanted them, then they got a booster. But in some low-income countries, the percentage of people who had even one vaccination was very low, and we were not doing enough to make the vaccines available all around the world, even though it was in our own interest to stop new variants developing. But we still didn’t do it, we still thought about the short term and ourselves.

Harari: We are, historically speaking, in the best position to deal with poverty in respect to the resources we have. For much of history, poverty and the effect of poverty (such as famine and such as infectious diseases and epidemics spreading) were like uncontrollable forces of nature. Humanity simply did not have the scientific knowledge and the economic resources to overcome things like famine and plague. There were no technological means to bring food from far away and with epidemics even more so, nobody knew anything about viruses or pathogens, let alone vaccines.

Now, for really the first time in history, these are no longer uncontrollable forces of nature. We have the scientific knowledge, the technology and the economic resources to make sure that no human being dies from starvation, or no human being dies from a long list of infectious diseases. Unfortunately, it doesn’t mean we always have the wisdom and the compassion to use these resources. So, on the one hand, we are in the best of times. Now it’s in our power, we can solve it. On the other hand, if we don’t do it, it’s an even bigger tragedy.

“People are unaware of the relative ease and modest amounts of money needed to be able to make a big difference in the lives of poor people.” (Peter Singer)

Singer: We choose not to see, relatively easily. When I talk to people about poverty elsewhere in the world, people who have no particular background in this area, they are likely to say, “Oh yes, I know that there are a lot of people who are very poor and their lives are very tough, but how can we help them? The money never reaches them. It’s like pouring it down a black hole.” People say to me things like that. I think the blind spot, therefore, is the knowledge of how relatively easily and for relatively modest sums of money we can make a big difference to the lives of people in poverty. We can save their lives by distributing bed nets, so they don’t get malaria. Or we can restore their sight if they’re blind because they have cataracts. If people are living on less than $2 a day, which is the World Bank’s extreme poverty line, and you give them $1,000, you’ve given them more than their annual income. That, of course, makes a huge difference to their lives. Whereas, when we’re helping people at home, but if the poverty line, say, is $20,000 as it is in the United States, for a family anyway, and you give them $1,000, it might make them a little more comfortable for a while, but it’s not going to be life changing in the way that it will be for somebody for whom it’s their entire annual income. I’m not sure whether people don’t know that, or they look away, or they don’t believe it because then they would feel more of an obligation to get serious.

Restore confidence in institutions

Harari: I think that, again, part of the problem here goes back to the institutions and the lack of trust in institutions. Because many people would say, if with $1,000 I could save the life of a person or the eyesight of a child, then yes, I would gladly do it, but I can’t do it myself. There is always an institution in between. A lot of people develop a deep mistrust and cynicism about institutions. “No, it's just some sham. All the money goes to the executives. It’s corrupt.” In the end it’s largely a question of how you build trust in institutions. Because most ideals, in order to be realised, can’t be done individually. Globally, the only thing that really works are institutions. And for that, people need to trust institutions.

Singer: That’s exactly what the charity The Life You Can Save tries to tell people how their money can be used specifically for a certain reason or cause. What we’re trying to show is that there are independently assessed charities that have been evaluated to be highly effective and to make the best possible use of any donation they receive. If they click on a button to donate, 100% of what they donate will go to those charities. They can feel confident that what they’re donating is really being highly effective.

Illustration. © Susana Blasco / Descalza

Illustration. © Susana Blasco / DescalzaHarari: In a situation where we are flooded by enormous amounts of information, what we need are institutions that curate information and recommend to you that institutions you can trust. And the question is, how do you learn to trust this institution? There is no way to bypass it. Any attempt to bypass institutions and say, “No, we don’t need institutions, we’ll just have some blockchain technology which will do it,” doesn’t work. The really important, difficult, but really crucial work is to build institutions that people can trust in.

Singer: Yeah, I think that’s right. Even with the internet we have places like Kiva where you can see a particular person who you want to donate to, but that’s not more reliable because there are some people who will take advantage of that and will pretend to be someone they’re not to receive donations that way. So, I agree, you do need an institution that you can trust.

Harari: That’s the problem. We actually need the institutions more than ever, but there is this wave of distrust against them. Maybe we need new media institutions which will be more diverse, which will give more people a chance to voice their opinions.

Effective altruism

Mudrik: Charity tries to do exactly that, to act like the gatekeeper or information provider that would help people to be more effective in their altruism. A paper written by Peter Singer, “Famine, Affluence and Morality”, inspired this idea or movement of effective altruism. Maybe you can explain what effective altruism is.

“The emphasis on effectiveness is the new topic of the effective altruism movement. These are people trying to figure out which are the best causes to make a donation to.” (Peter Singer)

Singer: People will know what altruism is. They know that it’s wanting to do good for others, and that’s been around for a long time. But the emphasis on effectiveness is what is new about the effective altruism movement. It’s about people who are trying to find out the best causes to donate to, and within those causes, the best organisations to support. It has become a quite extensive debate with a lot of different voices. Some people think that trying to help people in extreme poverty is one of the most effective things you can do. Others think that it’s trying to stop the suffering of animals, particularly the billions and tens of billions of animals now existing in industrial factory farms… Other people point to the risks that our species will become extinct.

Harari: Maybe I would just add that we just need to be careful not to turn this into an argument about what is the most effective. There is room for everybody. If somebody thinks that the most effective is to take care of animal suffering and somebody else thinks, “No, we should help people in poverty”. Focus on doing what you think is most effective, don’t try to convince the other guys that they are wrong, there is enough for everybody.

Mudrik: Perhaps the idea that there are so many ways to improve the world, so many problems, and that we can’t solve them all, has a paralysing effect.

Singer: I think it would be a pity if that happens. If people get involved in some of these issues and feel that they are achieving something, it adds meaning to their lives. In this material world, particularly people who have been reasonably successful at providing for themselves and their family in material terms, lack a sense of purpose. I think finding a cause that is really worthwhile is probably the best thing that you can do, for those you are doing good to, but also for yourself.

“No one person can do it all. So instead of being overwhelmed by the sheer number and scale of the problems, choose one that is close to your heart”. (Yuval Noah Harari)

Harari: I agree that it’s best you don’t choose one thing. Obviously, you can't do everything. Nobody can do everything. So instead of being paralysed and overwhelmed by all these different issues, just choose one issue which is close to your heart and then try to choose compassionately. Going back to some of the historical issues with altruism and with ethics, you see people that they focus, they try to do good through the most controversial means. I’ll give an example: you’re a Christian fundamentalist and you can choose whether to help the poor or whether to fight against gay marriage, and you choose to fight against gay marriage. So why not choose the kind of thing that everybody would agree on, nobody would become upset with you? Why choose the one thing that is bound to at least cause controversy, and that could cause a lot of suffering to some?

Singer: We’ve had similar debates on other issues with Christians too. In Australia, we have had over the last two or three years, a lot of debates about legislation to allow people to choose to die when they are terminally ill. Obviously that is, like gay marriage, adults consenting, and a person who wants to die, and a doctor who’s prepared to help that person to die. And we have now, in most of the Australian states, legalised that. But it took quite a battle, and the Christians were at the forefront of opposing it. Although it seems to me that it clearly reduces suffering, and it doesn’t harm people who don’t want it. Nobody is being forced to choose assisted dying. I think it’s strange that people should put a lot of energy into fighting things that competent adults are choosing and which doesn’t seem to really harm anybody.

Harari: I can understand why they oppose it. What I find kind of objectionable is the immense amount of energy invested in it. There are so many people who want to live, and you can help them live, instead of focusing on the relatively few cases of people who want to die, and you pour your resources into preventing them. Now there are so many people who really want to live, but they don’t have enough food or medicine, and you can really save them by pouring the resources there. So, wouldn’t it be kind of easier and more compassionate for everybody to just focus on that?

Mudrik: I guess history is filled with cases where people don’t go along the routes that you’re suggesting to them, and choose to fight those battles that you’re here fighting again, like the ones you were describing. And as a historian, you probably have an explanation to why that happened.

Yuval Noah Harari: The suspicion is that there is something other than compassion that dominates. There are political interests involved or there are all kinds of dark psychological forces, like hatred and bigotry. It could be that there is some compassion there as well, but diluted with a lot of hatred and anger. We know that people are almost addicted to this righteous anger, to proving that they are better than others, to having these arguments about who is right and who is wrong, instead of focusing on your belief and doing what’s right according to it.

Illustration. © Susana Blasco / Descalza

Illustration. © Susana Blasco / DescalzaMudrik: You can find this anger also in the type of initiative that you two have been involved in. For example, in the fight for animal rights. Here you have people who strongly fight to convince everyone else that they shouldn’t eat animals.

Singer: It does exist, but I think it can be based on compassion and concern for those animals and to the vast amount of suffering that we humans inflict on animals. I know Yuval agrees with me because he very kindly wrote a preface to my book Animal Liberation in a recent edition, in which he said that what we do to animals, particularly on industrial farms, is perhaps the worst crime that humanity has committed. I was moved by those words. So, I think if we’re talking about scale of suffering, it’s very reasonable to be focused on animals. It’s true that some people in the animal rights movement get rather fanatical. That seems to me to be missing the point. In fact, there are much bigger issues, so much more suffering that you could prevent if you targeted other targets.

Harari: I completely agree. If you have an animal rights activist and somebody says, “Okay, I decided to have a meatless Monday, I don’t eat meat on Mondays,” and then you attack them, “But what about all the other days of the week?”, I don’t think that’s the way to go. If somebody makes a step in the right direction, focus on the positive thing. People have an obsession with food that can go to extremes, like not even eating any honey that came from bees. I think we should have a broader view of the type of impact we have on animals and on the ecological system and not have a type of tunnel vision, just about food. We are obsessed with what we put into our mouths. Again, very often the last thing that remains from religion is food taboos. Like you have Jews, they don’t believe in God, they don’t go to the synagogue, nothing. But they won’t eat pork. Or they will fast on Yom Kippur.

Mudrik: What is the moral imperative? Given the assumption that we can’t do everything. What is the minimal thing that I, as an informed human being, should do when I conduct myself in the world?

“Try not to support a system that inflicts great suffering on animals. Industrial farms waste the food we have in order to feed those animals. This has implications for climate change and possibly also for the pandemic.” (Peter Singer)

Singer: If you’re a middle class – or above – citizen of an affluent country, you’ve got some money to spare, and you should be thinking about using some of that to help people in extreme poverty. It’s very hard to say how much. It varies, of course, not just with income, but with the dependence you have and so on. But the traditional 10% tie is not a bad standard to aim for. So that’s a start. I think you should be responsible for what you’re eating. But as I say, if you take various steps, I’m not going to be that critical. When my wife and I first became aware of the suffering of animals more than 50 years ago, we decided to stop buying factory farm products. That was our first step, and we continued to eat meat for a little while and then we decided that we didn’t really need it. In general, try not to support a system that is inflicting great suffering on animals, because factory farming just wastes the food that we have, to feed those animals. It has climate change implications and possibly pandemic implications as well. So, try to contribute to changing the world food system. And then of course, there are the general things about trying to be a decent person to those around you. I obviously don’t want to neglect them. I don’t think we just need to worry about distant strangers and animals.

Harari: It’s not about obeying this or that set of laws coming from above or coming from below, or wherever. Morality is about being aware of suffering and what we can do to alleviate it. The other thing is that morality tends towards moderation and not extremism. One of the big problems in the history of morality is that both secular and religious people confuse morality with extremism; that the more extreme you are, the better a person you are. You see it in so many different movements. But morality tends towards moderation.

Mudrik: Yuval, humanity has widened the scale. Would you say that humanity becomes more moral and more compassionate with time, or am I too optimistic here?

Harari: Most of the big changes in history are not uniform. You see the feminist revolution and the very fast changes and positive changes in attitudes towards gender and towards women. At the same time, you see the ecological crisis and they are happening at the same time. They don’t cancel each other out; they don’t add up. Over the long term, I think we cannot say that there is any marked improvement in human morality, because even the very real achievements of the last century, are just the last century, and who knows what’s waiting for us in 10 or 20 or 50 years? This could be just a very small blip in history.

Humanity is becoming more and more powerful and unified over thousands of years: not in the sense that everybody agrees or there are no wars, but everything becomes just a single system. From a situation with thousands of independent, isolated tribes, we now have one global system. But we can’t say that we see any clear improvement in human morality or any clear improvement in happiness either. We are not significantly happier. There is no clear trend towards better lives over thousands of years.

Maybe the pendulum just swings far between extremes. Look at the totalitarian regimes of the 20th century; they reached a depth of cruelty that may not have been reached anywhere previously in human history. Again, in the last few decades, the pendulum swung in a positive direction, but now in the last few years it’s again swinging in a very dangerous direction. Maybe in 20 or 50 years we could have totalitarian regimes worse than anything we’ve seen in the 20th century.

Singer: I certainly hope you’re wrong about that.

Harari: I also hope I’m wrong. It’s just a possibility, it’s not a prophecy. But we should be realistic that it is a possibility. It depends on us, on the decisions we take, on who we vote for and what kind of institutions we support. I mean, it goes back to the beginning of this talk. We are still in the position that we can do something to prevent the worst-case scenarios.

Recommended publications

Peter Singer: The Life You Can SaveRandom House, 2009

Peter Singer: The Life You Can SaveRandom House, 2009 Yuval Noah Harari: Sàpiens. Una breu història de la humanitatEdicions 62, 2016

Yuval Noah Harari: Sàpiens. Una breu història de la humanitatEdicions 62, 2016

The newsletter

Subscribe to our newsletter to keep up to date with Barcelona Metròpolis' new developments