Unwanted loneliness: when being connected isn’t enough

- Dossier

- Apr 23

- 8 mins

Unwanted loneliness is not just linked to ageing. On the contrary, some studies reveal that it is young people who suffer from loneliness more frequently, despite their greater sociability and access to technology. This makes the distribution of loneliness U-shaped, with a higher prevalence at the population’s two extremes of age. During adolescence, if this feeling is prolonged or chronic, it can bear negative consequences for health and well-being.

Unwanted loneliness is hardly a new topic. The first research on the subject dates back to the 1950s,[1] although it mainly refers to the isolation of older people. At the beginning of the 21st century, studies on unwanted loneliness and its consequences on physical and mental health began to grow.[2] But it was in 2018 – when Theresa May, then Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, set up the first Minister for Loneliness[3] – that it went beyond the academic and scientific realm and became a matter of public debate. This move raised concerns about loneliness, which affects nine million people in the UK, and launched a national strategy to understand and prevent unwanted loneliness, as well as to care for those suffering from it. In the same year, the European Commission issued a report indicating that 30 million people in Europe often felt lonely.[4]

Notwithstanding the evidence of these figures, we tend to see unwanted loneliness as a problem restricted to older people. This is perhaps because we associate loneliness with being alone, and we know that a large number of single-person households are made up of people over the age of 65, especially women. However, feeling lonely is not the same as being alone. A person can be alone and enjoy being alone. Conversely, there may be people who, despite living in the company of others and having regular social contacts, feel lonely.

The nature of loneliness

So what do we mean when we talk about unwanted loneliness? One of the most commonly used definitions considers this feeling to occur when there is a mismatch between the quantity and quality of the social relationships that we have, and those that we want.[5] In other words, the feeling of loneliness is not only determined by the number of relationships we have, but also by our perception of the quality of these relationships. Not having anyone to confide in, feeling neglected or excluded, having a feeling of emptiness, etc., may be the manifestation of this feeling of loneliness. This malaise, therefore, can appear at any life stage. In fact, it often manifests itself at times of transition in life, such as the change between stages of education, a move to another city or country, separation from a partner, widowhood, the beginning of parenthood, becoming unemployed or retiring, suffering from serious chronic illnesses, becoming a dependent person or becoming a caregiver…[6] Loneliness, therefore, has no age.

In 2009, Pearl Dykstra published an article debunking the myth that unwanted loneliness only affects older people. On the basis of survey data and longitudinal studies, she showed that unwanted loneliness is not necessarily an inevitable part of ageing, and that it can vary significantly between individuals and at different life stages. According to the study, it is young people, followed by older people, who feel lonely most often. This U-shaped trend (both extremes of age in the population) has also been found in surveys in countries such as the United Kingdom, Australia, New Zealand, the United States and Japan. In 2021, a study by Barcelona City Council[7] revealed a higher prevalence of loneliness among young people in the city of Barcelona: the population between 16 and 24 years of age feels lonely most often (7.1%), followed by people aged 25 to 34 (4.7%) and those aged 65 and over (4.1%).

If we focus on even younger people, teenagers, the figures for unwanted loneliness almost double: 12.6% of people in Barcelona aged between 13 and 19 say that they frequently feel lonely.[8] Adolescence is said to be, in itself, a stage in which the feeling of loneliness is often palpable and is linked to times of searching for identity. But if loneliness is prolonged or chronic, it can bear negative consequences for adolescents’ health and well-being, such as increased stress and social isolation, reduced cognitive capacity, self-centredness or a sense of threat from one’s surroundings.

Can we talk about the same kind of feeling of loneliness in adolescents, young people and older people? The feeling of malaise and emptiness might be similar, but the nature of this loneliness might be different. While the feeling of loneliness in older people is often related to a lack of social relationships (excessively small social network or poor-quality relationships) and poor physical and mental health (chronic illness, dependency, stress or depression, which hinder social relationships), it does not seem to be linked to the number of relationships held among younger people.

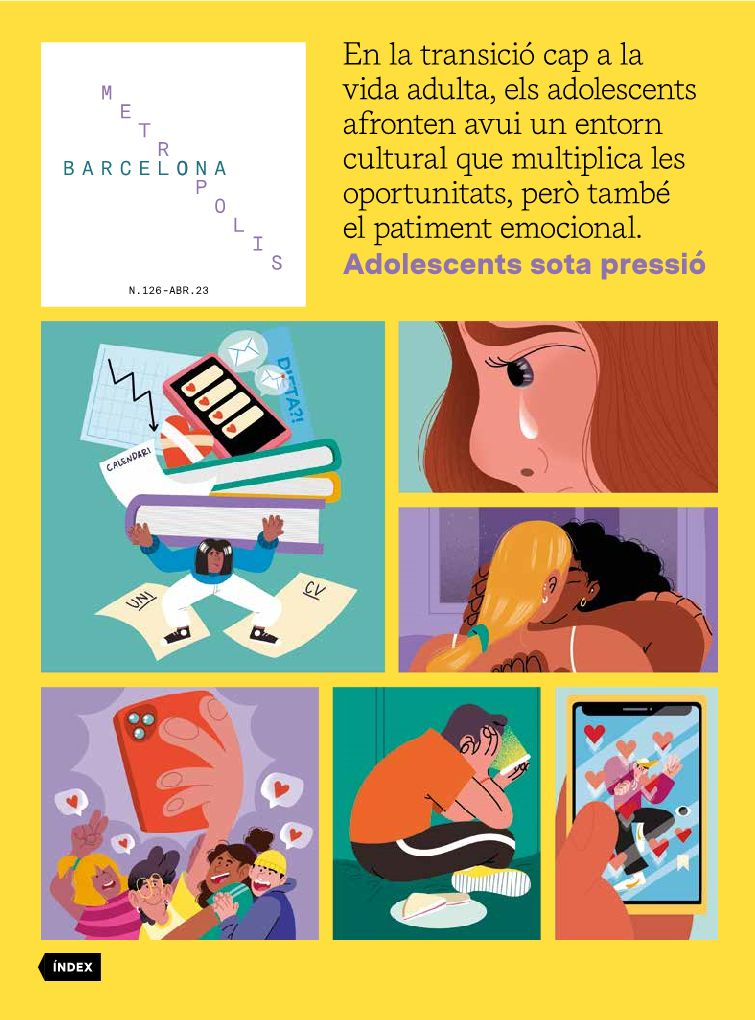

Il·lustració. ©Genie Espinosa

Il·lustració. ©Genie EspinosaUnwanted loneliness during youth is related to the transition to adulthood and the failure to achieve what is expected in this life stage.

Unwanted loneliness among young people seems to be related to frustration over certain issues linked to the transition to adulthood. Young people who have not emancipated, those who are unemployed, those without their own income and those without a stable partner are those most at risk of often feeling lonely. Therefore, we could say that unwanted loneliness during youth is more closely related to the failure to have attained what society expects young people to achieve in this life stage (becoming independent, having a job and their own income, or starting a family).[9]

For adolescents, unwanted loneliness is also linked to the frustration associated with youth, especially pronounced in the transition process between stages of education (educational and social pressures, change of friends and school environment, times of decision-making in the educational and professional path pursued, etc.). But also the need to fit into a group as a form of identity. The lack of a sense of belonging or the lack of quality relationships with peers and teachers may be a factor associated with unwanted loneliness in this life stage.

The use (and abuse) of screens

Another matter that has recently sparked debate among adolescents (as well as at other life stages) is the use (and possible abuse) of screens. Some research shows a link between the use of digital social media and unwanted loneliness. Although there is a positive correlation between face-to-face social relationships and virtual social relationships (adolescents with more face-to-face relationships also have more virtual relationships), there is a higher risk of loneliness when adolescents have fewer face-to-face relationships, but more digital social relationships (in the virtual space). The focus, therefore, should not so much be on avoiding the use of digital social media (there is no point in considering them as enemies), but rather on fostering personal relationships.

It is not a question of increasing the number of relationships, but of strengthening them, ensuring that they are meaningful, are at hand when needed and inspire trust.

In short, unwanted loneliness is a global problem in today’s societies, the outcome of the process of modernity, the rise of individualism, urban development and design, and the burgeoning use of technologies in a digitalised world. It can affect anyone, of any age, but some individuals are more susceptible than others depending on their life stage and the situation in which they find themselves. Therefore, the support and care that can be offered to those who feel lonely should take needs into consideration given the variability of factors that determine unwanted loneliness.

In the case of adolescents and young people who feel lonely, it is not a matter of increasing the number of relationships. They are already sufficiently connected and have a perfect command of how digital social media work. They need to be able to strengthen and build quality relationships, which are at hand when needed and that inspire trust. But much can also be done by social organisations and institutions, or even by society at large. Some actions could focus on promoting counselling and support measures, both economic and social, so that adolescents and young people can achieve their goals, so that they feel supported in their decision making and in times of frustration, generating spaces (physical or virtual) to share experiences, concerns, needs, failures and achievements, so that they understand that they are not (we are not) alone. Because fighting unwanted loneliness is up to all of us.

[1] Reichmann, F. F. “Loneliness”. Psychiatry, 22(1): 1-15. 1959.

[2] Cacioppo et al. 2000, 2002, 2006.

[3] In 2021, Japan also announced the appointment of a Loneliness Minister. http://ow.ly/tAgi50MGlEY

[4] European Commission (2018). Loneliness – an unequally shared burden in Europe. http://ow.ly/9vQN50MGm8N

[5] Peplau, L. and Perlman, D. (1982). “Perspectives on loneliness”. In Loneliness: A Sourcebook of Current Theory, Research and Therapy. New York: Wiley.

[6] A connected society. A strategy for tackling loneliness: laying the foundations for change. London. HM Government, 2018. http://ow.ly/sEy150MGmeL.

[7] Barcelona City Council (2021). Municipal Strategy Against Loneliness. http://ow.ly/ZZVS50MGlSE.

[8] Agència de Salut Pública de Barcelona [Barcelona Public Health Agency], 2022. http://ow.ly/3XiM50MGlVk.

[9] Marí-Klose, M. and Escapa, S. “La soledat de les persones joves”. In La Joventut de Barcelona l’Any de la Pandèmia. 10 anàlisis de l’Enquesta a la Joventut de Barcelona 2020. Barcelona City Council, 2021.

References

Dykstra, P. “Older adult loneliness: Myths and realities”. European Journal of Ageing 6, 91-100. 2009: http://ow.ly/1jS750MGlZq.

Cacioppo, J. T., Chen, H. Y. and Cacioppo, S. “Reciprocal Influences Between Loneliness and Self-Centeredness: A Cross-Lagged Panel Analysis in a Population-Based Sample of African American, Hispanic, and Caucasian Adults”. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 43, 1125-1135. 2017: http://ow.ly/lcga50MGnou.

Eccles, A. M. and Qualter, P. “Review: Alleviating loneliness in young people – a meta-analysis of interventions”. Child and Adolescent Mental Health 26, 17-33. 2020: http://ow.ly/bnRj50MGnMt.

Goossens, L. “Loneliness in adolescence: Insights from Cacioppo’s evolutionary model”. Child Development Perspectives 12, 230-234. 2018: http://ow.ly/Zmpj50MGnsW.

Hawkley, L. C. and Cacioppo, J. T. “Loneliness Matters: A Theoretical and Empirical Review of Consequences and Mechanisms”. Annals of Behavioral Medicine 40(2), 218-227. 2010.

Santini, Z. I. et al. “Social Disconnectedness, Loneliness, and Mental Health Among Adolescents in Danish High Schools: A Nationwide Cross-Sectional Study”. Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience, 15, 632906. 2021.

Twenge, J. M., Spitzberg, B. H. and Campbell, W. K. “Less in-person social interaction with peers among U.S. adolescents in the 21st century and links to loneliness”. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 36 (6), 1892-1913. 2019: http://ow.ly/WwmI50MGnwN

The newsletter

Subscribe to our newsletter to keep up to date with Barcelona Metròpolis' new developments