The MUHBA undergoes expansion, beckoning reflection on the city’s history

- Urban visions

- Jan 24

- 9 mins

The Barcelona History Museum (MUHBA) commemorates 80 years of igniting a fascination for contemporary Barcelona, expanding its reach to various locations within the municipal territory, and boosting its online presence. All this coincides with a moment of reflection on the role museums, specifically those dedicated to the history of cities, should assume in response to the emerging perspectives brought about by digital transformation.

The year 2023 has been noteworthy for MUHBA. Coinciding with its 80th anniversary, the museum is given a renewed impetus that is manifested both conceptually and organisationally. Key highlights include the opening of eight refurbished or expanded MUHBA venues, the presentation of research breathing new life into Barcelona’s historiography, and the adoption of collaborative management models involving the local community.

The Barcelona History Museum is a unique phenomenon on almost every level, an assertion I will explore shortly, confirmed by a brief glance at its online presence. Overstating the extent and peculiarity of this phenomenon is no small task, and capturing its essence in a few words is equally challenging. In this context, I take two approaches, neither particularly original, yet I hope they will resonate with a broad audience. Firstly, I delve into the dynamics within the realm of city museums and explore MUHBA’s connection to this wider context. Secondly, I endeavour to distil the key elements contributing to MUHBA’s success and provide brief insights into its future prospects[1].

The museum debate

In the wider world, there has been considerable debate regarding the direction various types of museums should take, with a backdrop of self-reflection gaining momentum over the past decade. All forums, from the International Council of Museums (ICOM), represented by CAMOC (the specific body established for municipal museums within ICOM in 2005), to the City History Network set up by the museums of Amsterdam and Barcelona in 2010, have deliberated on the purpose of these establishments, regardless of their nature.

The ICOM debate came to a head over the definition of what constitutes a museum, taking several years to reach a consensus on this new definition, ultimately achieved in 2022[2]. Key considerations include placing emphasis on ethical judgments regarding current pressing issues, notably forms of colonisation and decolonisation, and the treatment of recent migration. Additionally, there is a focus on the degree of movement towards collaborative “co-creation” of museums, as opposed to more traditional management approaches by professionals.

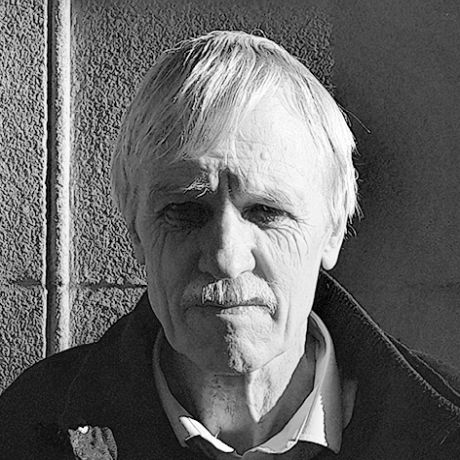

In my view, MUHBA, whilst fully aware of and wholly engaged in these debates, has achieved its recent successes by charting its own path, drawing on the social and political strengths of Barcelona’s society. Since its inception, spanning decades, these strengths have been instrumental in cultivating the museum’s power. However, in the last fifteen years, Joan Roca’s leadership has significantly strengthened these foundations. This success is attributed to Roca’s strategic vision – a plan that adapted to evolving circumstances over the years but was clearly defined from the outset. Naturally, this strategy was impacted by an array of unforeseeable factors, including municipal politics, resource availability, the varying emergence of collaborators across all domains, and the ongoing integration of intellectual and academic insights.

MUHBA’s principles are founded on the emphasis on the “democratic majority”, specifically involving expanding the reach of museum activities to cover the entire city, not solely focusing on privileged areas of the historic centre and other somewhat incidental hotspots, as is customary in most European municipal museums. This emphasis, while consistent with the content of numerous ongoing debates across the museum world, does not really share the same starting point nor, for that matter, aim to reach the same conclusion.

Passageway in Refugi 307 in Poble-sec, a shelter built during the Spanish Civil War. © Imatges Barcelona / Josbel A. Tinoco

Passageway in Refugi 307 in Poble-sec, a shelter built during the Spanish Civil War. © Imatges Barcelona / Josbel A. TinocoClearly, the emphasis is placed on issues specific to municipal museums, spaces and the histories of the city concerned, rather than the somewhat more predictable content found in art, science, nature or technology museums. This has especially nuanced the “everyday” aspects of urban living, delving into matters such as housing or employment, as well as social, ecological and implicitly political aspects – although more “cultural” factors, such as religion and the realm of ideas, have by no means been excluded. Perhaps the focus lies in a widespread anthropological idea of “culture”, with a broad scope, as advocated by the tradition of the Welsh writer Raymond Williams in the 1960s and 1970s. MUHBA’s approach tends to be depicted on a much bigger canvas than what most municipal museums across Europe, that I am familiar with, have used.

When it comes to method and process, in contrast to content, MUHBA’s distinctive trajectory is clearly discernible. The approach is inspired by a kind of democratic academy, accessible to all citizens interested in contemplating their history and its connections to the present and future – a fundamentally collaborative strategy, in other words. Participants gather together in dialogues, seminars and exhibition projects to collaboratively and rigorously create a core criterion. Indeed, I haven’t come across this model elsewhere, making it appear home-grown. It might be common sense that successful innovative approaches emerge from deep and fertile ground, perhaps even more so than from global or overly general rhetoric and arguments. However, the home-grown approaches of most European cities have not necessarily had this deep and fertile ground or achieved the same results.

MUHBA’s success

The major areas of progress in the past fifteen years combine substance with method. Collaboration is a key ingredient in the formula, both within MUHBA and in society at large. Nevertheless, resource constraints pose a challenge to maintaining this balancing act. It also appears that administrative and financial regulations further complicate the task of museum management.

In my view, MUHBA’s spatial and geographical transformation marks a pivotal moment, particularly with the creation of the Besòs axis of centres and activities, involving specific work with districts and associations in this area. This dimension is also reflected in the strategic direction that, since the 1980s, has aimed to regenerate and reshape the nature of this area. Over many years, the endeavours of various stakeholders have facilitated the geographical rebalancing of Barcelona and, to some extent, the entire metropolitan area. In essence, MUHBA prepares the ground for changes, leveraging its capacity to reshape perceptions of past and ongoing transformations, rather than directly exerting transformative impacts – although the influence of certain museumising initiatives on housing, industry and water in the northeastern sector of the city should not be underestimated.

![A window in the Cases Barates [affordable housing units] in the Bon Pastor neighbourhood, in the new facilities of the MUHBA’s Museu de les Cases Barates del Bon Pastor. © Imatges Barcelona / Edu Bayer A window in the Cases Barates [affordable housing units] in the Bon Pastor neighbourhood, in the new facilities of the MUHBA’s Museu de les Cases Barates del Bon Pastor. © Imatges Barcelona / Edu Bayer](https://www.barcelona.cat/metropolis/sites/default/files/styles/img_flotada/public/bm_129_visions-urbanes-muhba_02_ample-555_finestra_cases.jpg?itok=s_I2V3Uc) A window in the Cases Barates [affordable housing units] in the Bon Pastor neighbourhood, in the new facilities of the MUHBA’s Museu de les Cases Barates del Bon Pastor. © Imatges Barcelona / Edu Bayer

A window in the Cases Barates [affordable housing units] in the Bon Pastor neighbourhood, in the new facilities of the MUHBA’s Museu de les Cases Barates del Bon Pastor. © Imatges Barcelona / Edu BayerAs an urban planner, I am especially interested in the impact this phenomenon has on the “spatial imaginaries” that citizens have of their city. Of course, this includes politicians and architects, along with other influential figures in urban transformation. It would be interesting to compare how people viewed the city (and beyond) two decades ago with how they see it now, in terms of images, mental maps, and so on. Methodologically speaking, such a comparison poses quite a challenge, with identifying the impacts of MUHBA’s work presenting an even bigger one. Essentially, this constitutes a noteworthy challenge for urban geographers, sociologists or ecologists.

Building and sharing knowledge

In my view, the second noteworthy accomplishment revolves around building and sharing knowledge. This is tied to MUHBA’s academic and collaborative framework, which engages in a substantial volume of work related to research and presentation. The museum has actively collaborated with academic experts and local associations, over not just a year or two but rather one or two decades, contributing to the advancement of knowledge on subjects such as food supply, water provision and housing issues. Notably, there have been considerable publications on these subjects, in both extensive and concise formats, with some being highly accessible and available in several languages. This publication initiative is, in my opinion, unmatched by any other museum, at least in the realm of municipal museums. Of course there is plenty of scope for the future teams at MUHBA to expand this approach into new foundational fields and through innovative approaches.

The transformations at the museum’s main seat in Plaça del Rei are also a significant achievement, not only because they are the most visited and visible, but because they have laid the groundwork for future MUHBA teams to use these spaces as foundations for their projects without the need to modernise the basic infrastructure, a task that has already been completed.

A fourth achievement would be the quality of the online presence. I would say that MUHBA fares very well when compared to the websites of other European municipal museums I know, both in terms of adaptation to changes over the years and the depth of information it provides. A good example is the cartographic element, which continues to spread and flourish, enabling anyone worldwide to access and interact with the historical geography of Barcelona, a boon to scholars and the general public of all ages and backgrounds.

Obviously, talking about the future is much riskier than summing up the achievements to date. Presumably, the museum will strive not to rest on its laurels or halt its evolution and progress. However, it would be quite natural for the dominant theme in the coming years to focus on consolidating certain elements that have been achieved. When it comes to learning about the new centres on housing, labour, water and urban development, it will be important to experiment with how new understandings within each topic evolve and how connections are made between the museum’s different “rooms”: 55 rooms, distributed across a total of 18 centres.

[1] We cannot add much to what the current director, Joan Roca i Albert, has already said about MUHBA’s progression over the years. Compiling all these reflections into a book would significantly contribute to future thinking.

[2] “Un museu és una institució permanent no lucrativa al servei de la societat que cerca, col·lecciona, conserva, interpreta i exposa llegat tangible i intangible. Els museus, oberts al públic, accessibles i inclusius, promouen la diversitat i la sostenibilitat. Operen i comuniquen de manera ètica, professional i amb la participació de les comunitats, i ofereixen experiències variades per a l’educació, l’entreteniment i la compartició de reflexions i coneixements.” icom.museum

MUHBA’s heritage spaces

MUHBA has expanded its network with the launch of the Conservation and Restoration Centre, which includes the Archaeological Archive and the renovation or incorporation of new heritage centres distributed throughout the neighbourhoods and districts of Barcelona.

Ciutat Vella

El barri Gòtic

MUHBA Casa Padellàs

MUHBA Plaça de Rei

MUHBA Temple d'August

La Porta de Mar i les Termes Portuàries

MUHBA Via Sepulcral Romana

MUHBA Domus Avinyó

MUHBA Domus de Sant Honorat

MUHBA El Call

Sant Pere, Santa Caterina i la Ribera

MUHBA Santa Caterina

Sants-Montjuïc

El Poble-sec

MUHBA Refugi 307

Zona Franca-La Marina del Prat Vermell

MUHBA Centre de Col·leccions

Sarrià-Sant Gervasi

Vallvidrera

MUHBA Vil·la Joana. Casa Verdaguer de la Literatura

Gràcia

La Salut

MUHBA Park Güell

Horta-Guinardó

Can Baró

MUHBA Turó de la Rovira

Sant Andreu

El Bon Pastor

MUHBA Bon Pastor

Sant Andreu

MUHBA Fabra i Coats

La Trinitat Vella

MUHBA Casa de l’Aigua

Sant Martí

Provençals del Poblenou

MUHBA Oliva Artés

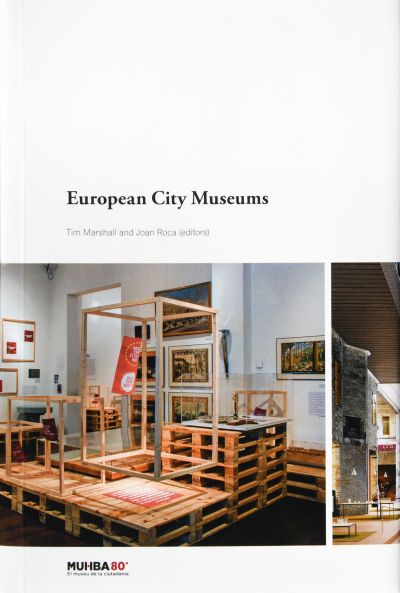

BOOKS BY THE AUTHOR

European City Museums Tim Marshall i Joan Roca Barcelona City Council and MUHBA, 2023

European City Museums Tim Marshall i Joan Roca Barcelona City Council and MUHBA, 2023 Transforming Barcelona Routledge, 2004

Transforming Barcelona Routledge, 2004

The newsletter

Subscribe to our newsletter to keep up to date with Barcelona Metròpolis' new developments