“The left has many believers, but few practitioners”

- Interview

- Apr 24

- 17 mins

Francesc Escribano

Francesc Escribano is a journalist with the soul of an anthropologist. In his youth, he grappled with choosing between these two professions, and over time, he has merged the finest aspects of both. From journalism, he retains a critical eye, the ability to disseminate information effectively, and an enviable talent for engaging with audiences. From anthropology, he has learned to listen without bias, with the attentiveness of an ethnographer and the curiosity of a scientist. Many recognise him as the former director of TV3, a role he held for four years. However, he readily admits that, in another life, he might bypass this chapter altogether. “I had to keep my phone on silent constantly because every time it rang, it drove me up the wall!” Even now, though he keeps his phone muted, his demeanour suggests a man deeply immersed in numerous projects, living with a profound connection to the world around him.

Francesc Escribano (Vilanova i la Geltrú, 1958) joined TV3 in 1981 as a news editor and eventually rose to become its director from 2004 to 2008. Among his extensive television work, he is best known for a range of documentary series that share a common premise: focusing on ordinary people and observing their everyday lives. This led to the creation of shows like Ciutadans [Citizens], Vides privades [Private Lives], Veterinaris [Vets] and the unique Generació D [D Generation], a project where he has periodically interviewed a group of individuals for over thirty years. In addition to his work in television, Escribano has authored books on Salvador Puig Antich, Antoni Benaiges, and Pere Casaldàliga’s Brazil, a country and a figure that fascinated him from a young age. Currently, he heads the production company Minoria Absoluta, through which he has produced projects like the miniseries Descalç sobre la terra vermella [Barefoot on Red Earth] and films such as El mestre que va prometre el mar [The Teacher Who Promised the Sea].

Did you always want to be a journalist when you were young?

Yes, absolutely! I made it clear to everyone who asked. I never pictured myself working in television, but I had a passion for journalism. I loved writing.

And you ended up studying Journalism.

Yes, I was thrilled when I started. But as I delved deeper into the field, I became disillusioned.

Why?

Because I saw how things were done… The first assignment I was given at the Vilanova newspaper, where I was trying to intern, was to attend a concert for which they had already written the review! They just wanted me to make sure that the concert was actually happening, lest they publish a review of a concert that never took place!

Did this disillusionment prompt a change in your plans?

Well, sort of… What I realised was that my calling was to be an anthropologist. But I wasn’t entirely sure either, mainly due to limited resources… If there had been more financial stability at home, I might have given up journalism to pursue anthropology. Yet, taking advantage of the laid-back university atmosphere, I decided to complete my journalism degree by focusing on anthropology topics for all my assignments. I attended anthropology seminars, devoured anthropology books incessantly… Anthropological texts just blew my mind.

How did your professional career begin?

In fact, my foray into the world of journalism stemmed directly from my interest in anthropology. At that time, there was a movement to reclaim and celebrate popular culture, festivals and folklore… And in Vilanova, it was particularly vibrant, thanks to figures like Bienve Moya, a prominent folklorist. There was a palpable enthusiasm surrounding this resurgence. So, I started contributing to a magazine called El món, writing a section focusing on festivals and local traditions, aiming to inject it with a touch of humour.

And how did you make the leap to television?

Well, that happened because Salvador Alsius came up with the idea to incorporate a segment into the Telenotícies [television news broadcast] dedicated to the saints of the day. Since I had a good grasp of the topic from my work at El món magazine, he sought me out to handle it. What’s more, the people at Televisión Española also approached me to do reports on popular festivals, which were seen as quite exotic at the time.

So, you ultimately managed to blend journalism with anthropology.

During my studies, I was convinced I’d never end up working as a journalist or in television. But thanks to the anthropological angle, that’s exactly where I found myself.

When you joined TV3, television was just starting to take off…

Yes, I came on board as a news editor in April 1984, right when the Telenotícies migdia [lunchtime news] began, and later moved to 30 minuts. There weren’t many people with experience in reporting, so given my background creating pieces for Televisión Española, I jumped right in. It was the early days of television, and much work lay ahead.

Portrait of Francesc Escribano © Albert Armengol

Portrait of Francesc Escribano © Albert ArmengolIt must have been exciting.

It was an incredible era! I believe we were lucky. In the early days of 30 minuts, we often asked ourselves: “What exactly are we doing? Reportages? Documentaries?”. Being in a situation where you’re not entirely sure of your role, and you have to figure it out alongside others, is exhilarating. We learned a great deal from each other. Remember I was only 25 years old. Nowadays, I’d be considered an intern. But back then, I was already out there, doing reportages… it was phenomenal. We were fortunate to live in a time when there were still unexplored avenues.

In your latest book, you mentioned that in 1985, Joan Salvat, the director of 30 minuts, sent you to Brazil to work on a “free-topic” report. How did that come about?

Well, what actually happened is so absurd that I didn’t even dare to include it in the book.

Wow, tell me about it now!

Well, a travel agency in Andorra and the local Iberia office in Girona organised a trip to Brazil for their employees. Then they approached us at the TV station, offering two tickets to accompany them and produce a report about their journey. We politely declined, as a corporate trip didn’t strike us as particularly newsworthy… However, back then, opportunities to travel to places like Brazil for reporting were scarce. So, we brainstormed on how to make use of the tickets they were offering us.

Eventually, we suggested to the agency that they bring local products to the Catalan community in Rio de Janeiro, providing us with a pretext to produce a segment for “Fets i gent”, a section in the Telenotícies. This secured us the two tickets; I used one to cover Casaldàliga, while Dolors Genovès interviewed Jorge Amado and explored Brasilia’s architecture with the other.

How did you come to choose Pere Casaldàliga as the subject of your documentary?

As I delved into research, seeking a compelling topic linked to Brazil, Pere Casaldàliga kept cropping up in numerous news articles. He lived in the jungles of Mato Grosso, a place I held in mythical regard, having been immersed in Claude Lévi-Strauss’s ethnographies. In addition, I learned that two of his nieces worked at TV3. The pieces fell into place quite naturally.

Were you aware of the significance Pere Casaldàliga would eventually hold in your life when you did that reportage?

No, not at all. At 26, my focus was primarily on myself. The magnitude of his impact didn’t register then. Yet, the experience deeply resonated with me. I feel in love with the country and its people… It left me longing to return. And that’s precisely what I’ve been doing ever since.

Anyway, in your books, you describe your initial encounter with Casaldàliga as quite impactful.

Casaldàliga had a way of drawing you in; it was something he did with everyone. He was one of those people who truly connected with you. It’s uncommon, don’t you think? Often, when we’re with someone, our minds wander elsewhere. But he possessed this remarkable quality: when he was with you, he was fully present.

The report almost resembles an ethnographic documentary.

Indeed, much of my work at TV3 was deeply influenced by my studies in anthropology. A significant number of the reports we produced on 30 minuts revolved around these themes, and the series we developed had a distinctly anthropological flavour.

Let’s talk about these series a bit. How did you get started?

For one of the segments on 30 minuts, we set out to find a group of 15-year-olds who represented the first generation born after Franco. It was all about capturing a generational snapshot, so we handpicked around seventy individuals and asked them the same set of questions. Salvador Cardús served as our advisor, and his input was invaluable in shaping the project.

Then, Joan Úbeda, a producer at 30 minuts, mentioned that the BBC was running a programme where they tracked a group of young people over the years, periodically filming them. That sparked the idea of interviewing these same individuals every seven years, which became the foundation of Generació D.

This marked the beginning of many programmes that clearly share a common thread.

Yes, because we noticed that the format of selecting a group of similar people and asking them the same questions worked really well. We created a series called Ciutadans, and from there, many others followed, all characterised by a common trait: observing the ordinary lives of anonymous individuals.

“It’s often our behaviour in ordinary situations that truly defines us. What we do on a daily basis.”

Journalists are often taught to focus on what deviates from the norm… A person biting a dog, rather than a dog biting a person.

We have the impression that our true nature is revealed in how we handle extraordinary situations, yet it’s often our behaviour in ordinary situations that truly defines us. What we do on a daily basis.

Most of the series we produced revolved around this: observing normality, the everyday lives of ordinary people… But elevating it to a position of importance. We would tell them, “What you do is interesting”. And when this works, it’s very revealing and powerful.

A chapter in your latest book is titled “Persones senzilles en llocs sense importància” [Simple People in Unremarkable Places].

Yes, this comes from an African proverb shared with me by Paulo Gabriel, a close friend of Casaldàliga. “Simple people, in unremarkable places, doing small deeds, are the ones who change the world”. Those doing modest tasks, but doing them well, are the ones who make a difference.

At a certain point, you began to take on leadership roles within the TV3 structure. How did that unfold?

As you reach a certain age within a large company, it’s almost inevitable… you start moving up. Those of my generation were among the first who, having started there, ended up in management positions.

What does it mean to be a director at TV3?

It means living under pressure. TV3 is expected to deliver on all fronts. I don’t want to discredit anything I’ve accomplished, but these are years where the pressure is so intense it’s overwhelming. You’re pulled in every direction: by politicians, by the audience, by the internal team… With such high levels of pressure, it’s hard to cope. After three or four years in the role, I remember asking myself, “Why on earth did I agree to this?”.

Why do you think you agreed?

There was this feeling of being part of a generation that had emerged from there and had something to offer… And perhaps a bit of self-deception, thinking, “Now we’ll truly make public television”. But TV3 is too significant, and the pressures are immense… I managed to endure it somehow. But if I had to make the choice again, I’m not sure I’d choose the same path!

Were you able to accomplish things you’re proud of?

Yes, many. One of the things that made me most proud is that TV3 wasn’t just like any other channel. We championed unique programmes that, what’s more, were successful. And that’s crucial because, in television, without an audience, you’re not serving the public!

“TV3 has to be a public broadcaster, and a public broadcaster has to set an example.”

You often talk about the importance of public television.

Yes, I’m deeply invested in this idea. There are people believe that merely being in Catalan, TV3 has fulfilled its role. But that’s not the case. TV3 has to be a public broadcaster, and a public broadcaster has to set an example.

What does “setting an example” mean to you?

Well, things like organising La Marató, for example. Or introducing new formats for programmes or airing documentaries like Sense ficció in prime time. TV3 has achieved this by building an audience and investing in it. My particular sensitivity during the eight or nine years when I held influence helped cement this approach. This distinctive aspect is what makes me most proud.

In any case, when your tenure as director ended, you left TV3.

Yes, because it was challenging for me to stay there after having had that level of responsibility. On paper, I always said I wanted to return to 30 minuts. But, in practice, it was very hard for me.

What I didn’t want was to join a production company that I had dealt with as director of TV3. So I went to Madrid and spent a year working with a production company where we focused largely on fiction. Then, due to family reasons, I had to return to Barcelona. Coincidentally, this was when Toni Soler wanted to set up a production company, and I joined the project.

Up to now, we’ve discussed television at length, but you’ve also authored several books. What role does writing play in your life?

When you write, it’s from the depths of your soul, inspired by topics that deeply resonate with you. Even though the writing process may be lengthy and laborious, it’s also incredibly gratifying. It’s a journey of self-discovery… And, despite the challenges, you enjoy it. For instance, my latest book has been instrumental in helping me understand why figures like Casaldàliga and Brazil were so significant to me.

And aside from your books, do you have a personal writing habit?

No, my background leans more towards journalism, where I write on assignment. Even if I’m the one assigning the task.

Let’s talk about the protagonists of your books: Antoni Benaiges, Salvador Puig Antich, and Pere Casaldàliga. What do they share?

They are all activists. Benaiges and Casaldàliga are activists of hope. All three are individuals who devote their lives to their beliefs, to the point where two of them go so far as to sacrifice their lives. It’s intriguing because Benaiges and Puig Antich, who didn’t seek death and weren’t aspiring martyrs, ended up as such. Conversely, Casaldàliga, who did harbour such aspirations, is the one who died of old age. His friend Tomás Balduíno would joke, “God will punish you by making you die in your bed!”. They joked about this because they were sure they would be killed before that. It was as if they were in a war, where the assumption was they wouldn’t survive. So, they planned to embrace death as the ultimate manifestation of giving life. Nonetheless, the level of activism, radicalism and commitment is similar in all three.

“We live in a world where superficiality is valued much more than activism.”

The fact that you’ve devoted so much to these characters, what does it reveal about yourself?

It tells me that I’m not at all like my biography subjects! And it suggests that what I admire in them might be what I lack, don’t you think? This spirit of activism, this dedication, this radicalism… Ultimately, all three are radicals, and you realise, “Gosh, embracing radicalism in life might actually be worthwhile!”. We live in a world where superficiality is valued much more than activism. We’re inclined to mistrust those who are deeply engaged in activism. But I believe that real change calls for activism.

Do you see yourself as a staunch advocate for a particular cause?

No… I see myself as someone who’s aware, but compared to these people, I can’t label myself as an activist… Casaldàliga used to say, “Believing isn’t enough; one must also be credible”. We often think that belief alone suffices, but what truly defines us is our actions. The key lies in living in accordance with our convictions. We live in a world where there’s a need for much more activism, not just belief.

During your last trip to Brazil, you saw this very clearly, didn’t you?

Yes, this trip was very enlightening in terms of understanding what’s happening on the left. Observing how Bolsonaro’s discourse has taken hold, I wondered: “Why is the message of the far-right gaining such momentum?”. And you come to the conclusion that, on the left, it’s a bit like with Catholics: there are many believers, but few practitioners.

Speaking of the far-right and Bolsonaro, your latest book reveals your surprise at seeing unexpected individuals embracing his rhetoric.

Well, the thing is, the far-right message, besides being delivered through very modern channels, is characterised by its emphasis on destruction, whereas the other is about building. So, depending on where you are in life, one message might appeal to you more than the other. There comes a time when you’re more inclined to hit the streets than to stay home waiting or take the longer road of construction.

© Albert Armengol

© Albert ArmengolBased on what you’ve witnessed in Brazil, what factors do you think sway people toward one path or the other?

I couldn’t tell you for sure… You know what’s happening? We live in a world where convictions are very fragile, so everything is very volatile. And, besides, political offers come to you via WhatsApp, through family group chats… Currents of opinion are created in this manner, and you end up thinking the same as your friends. In the end, it’s more emotional than rational. On the other hand, ambition also ends up being important. Ambition sometimes resonates with hope, but sometimes it resonates with speculation. Ambition often leads you to think that, to better yourself, you have to step on someone else.

Let’s talk about spirituality for a moment. You didn’t come from a particularly religious family background, did you?

No, I didn’t. I studied at a school run by the Christian Brothers, but my parents weren’t religious… It’s just that I’ve always been drawn to everything related to religion. I suppose it’s also tied to my interest in anthropology. Anyway, sometimes we think that spirituality is about who knows what… and I believe that spirituality is about what we were discussing earlier, what we should believe in and practise. I believe in many things. And what I’m certain of is that these beliefs should drive me to take action, to fight… Spirituality is a part of all this.

In Brazil, we can often see this association between struggle and spirituality.

Yes, absolutely. In fact, during my recent trip, some members of the Workers’ Party (PT) mentioned to me that one of the challenges the left had faced was losing this spiritual dimension. It’s true that the PT’s rise was closely intertwined with the emergence of liberation theology and undoubtedly had a spiritual aspect. It seems as though, in practice, without the guiding light of belief, it never quite clicked… This is particularly evident in the case of Casaldàliga. While his message could have stood on its own without the religious and spiritual elements, when you add this dimension, everything takes on a deeper significance.

Speaking of beliefs and commitments, could you share the story behind the ring you’re wearing?

It has its origins with African slaves who could not own gold or jewellery. So they crafted rings from a type of coconut found in Brazil called “tucum”. When Casaldàliga became a bishop, he chose to forgo the tradition of wearing a luxurious episcopal ring and instead opted for one made of tucum. This decision transformed the ring into a symbol of liberation theology, the indigenous cause, and the left… In Brazil, many people wear it; here, it bears no significance, but there, it carries great meaning. It’s often said that this ring isn’t something you buy for yourself; it must be gifted to you by someone else.

So, in your latest book, you mention how wearing this ring has been a reminder of your convictions during key moments. Did you wear it back when you were the director of TV3?

Yes.

And, as director, did you ever wonder what Casaldàliga would do in certain situations?

Hmm… Sometimes I did wonder, but often I didn’t dare to, because I probably wouldn’t have liked the answer! You need role models, but you can’t apply them strictly.

Lastly, describe your ideal day for me.

An ideal day starts in Vilanova, overlooking the sea and enjoying time with my granddaughters, who are three gems. I’m very fond of Vilanova, and right now, I’m at a stage where… how should I put it? My friend Guillem Terribas says, “Grandchildren are life’s dessert”. Well, I’m savouring that dessert right now!

Recommended publications

La terra i les cendres Edicions 62, 2023

La terra i les cendres Edicions 62, 2023 Desenterrant el silenci: Antoni Benaiges, el mestre que va prometre el mar Blume, 2013

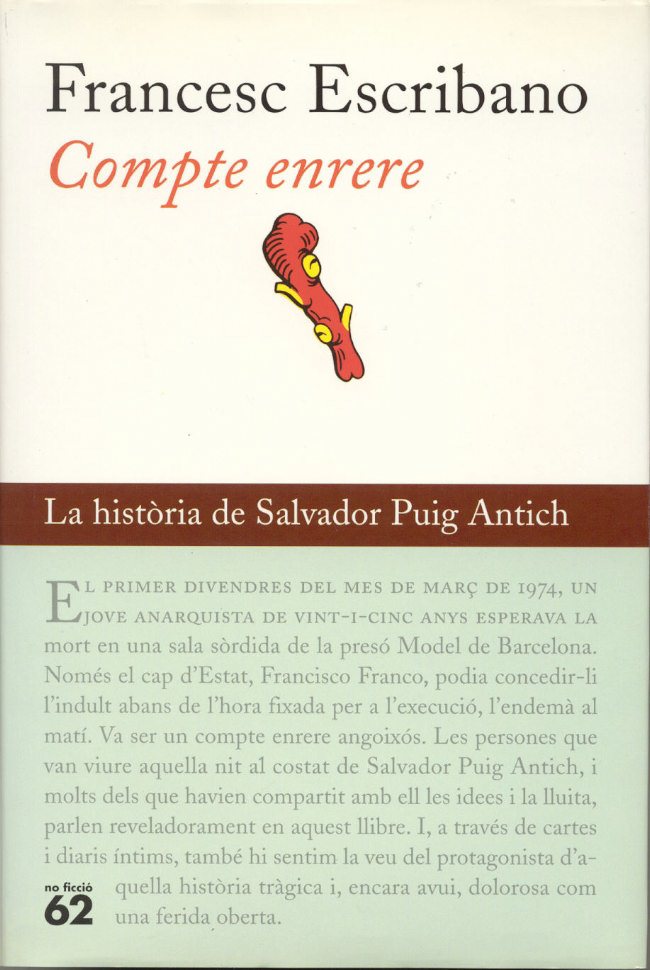

Desenterrant el silenci: Antoni Benaiges, el mestre que va prometre el mar Blume, 2013 Compte enrere: la història de Salvador Puig Antich Edicions 62, 2001

Compte enrere: la història de Salvador Puig Antich Edicions 62, 2001

The newsletter

Subscribe to our newsletter to keep up to date with Barcelona Metròpolis' new developments