Cultural audiences, are they passive spectators?

- Culture Folder

- Trends

- Apr 23

- 12 mins

The crisis of cultural audiences has made audiences a highly prized asset. Managers are striving to win them over, and some audiences are even calling for their role to be broadened. In the jargon of cultural management, there has been a shift from politics of access – so that people can go to the theatre – to access to the means of production – so that they can do things on stage. Perhaps the solution is for the audience to go from playing a passive role to being an active author of their own story.

We have been talking about cultural audiences for years. In this article, and owing to professional deformation, reference will mainly be made to theatre audiences, but it is an issue that affects other artistic disciplines (film, music, the visual arts, etc.). And I say problematic because it has often been regarded as “the audience problem”, as if the audience had a problem that did not affect the other agents in the cultural ecosystem, such as artists or managers. Jordi Oliveras, cultural activist and head of the Indigestió project, summed it up as follows in a discussion in 2015: “The idea that audiences need to be educated for culture is repeated in different spheres. This opinion is voiced among the world of cultural entrepreneurs and also among some creative circles, claiming that people need to be taught the basics to be able to relate to cultural production. It is often said that there is a lot of production and quality, but that the problem is the audience.”

For years, this subject has thus been the focus of numerous professional conferences, debates, public policies, European programmes, and articles and commentaries in specialised and mainstream publications. This year will mark the tenth anniversary of the creation, on the part of the Catalan Institute of Cultural Enterprises, of the Audiences Division, which devises and develops strategies for the promotion of cultural audiences (also known as “audience creation”). This division fosters subsidies for professional activities, the aim of which is precisely to increase the loyalty and the number of cultural audiences in Catalonia.

It seems, then, that if it occupies so much space and so many people and so many organisations work on it, that the problem is a major one. And according to the findings of studies, it is a widespread issue (at least across Europe, not only here) and it is not so much about economic hurdles (I don’t go to the theatre because I can’t afford to), as it is about interest (I don’t go to the theatre because I have no interest or because I don’t have time to go, which is the same thing, because the people who say this are never short of things to do).

The Escola de l’espectador del Teatre Grec [Teatre Grec’s Spectators’ School] was set up to facilitate an understanding of the concepts that help the audience to grasp the whys and wherefores of a play, a choreography or a show. ©Josep Aznar

The Escola de l’espectador del Teatre Grec [Teatre Grec’s Spectators’ School] was set up to facilitate an understanding of the concepts that help the audience to grasp the whys and wherefores of a play, a choreography or a show. ©Josep AznarBy way of example: at the end of 2022, Agost Produccions, an organisation specialising in cultural mediation, held an artistic awareness-raising workshop for secondary school pupils at a school in the Barcelona neighbourhood of La Bordeta, which was complemented by an outing to the theatre to see a show created and designed for young audiences. Well, all the pupils took part in the workshop (basically because it took place during school hours and they were obliged to), and very few went to the theatre that night, although the theatre gave them free tickets. Again, this is not a monetary issue. It’s as if these first-year secondary school students had something ingrained in their subconscious that told them “what you’re talking about doesn’t appeal to me”.

In this context, and to cite a few more examples, during 2022 a couple of gatherings on cultural audiences were held at La Muriel, a space in the Gràcia neighbourhood managed by the actor Pau Roca and his company Sixto Paz. What sparked the debates was inevitably the post-pandemic theatre audience crisis. Jaume Forés (from Núvol, the online culture magazine), present in the audience, pointed out that, before the pandemic, between 27 and 28% of the population claimed they went to the theatre at least once a year. After the pandemic, this percentage dropped to 20%. Also among the audience, the cultural entrepreneur Andreu Rami (from the online magazine Teatre Barcelona) pointed out a devastating statistic from the latest survey by the Institut de Cultura de Barcelona: the performing arts interest 6% of Barcelona’s population. Ninety-four per cent of the city’s population wouldn’t go to the theatre even if they were given free tickets and a red carpet. The actor Pau Roca, from the speakers’ panel, said, “I talk to lots of friends who don’t go to the theatre much, once or twice a year, and I get the impression that they don’t go because people need to ‘get their lives back’”. He went on to say, “and this happens mainly because of getting together again in bars and restaurants, and on outings with friends outside the city…”. Nevertheless, Roca was optimistic, and affirmed that “these people will come back”.

According to figures from the Associació d’Empreses de Teatre de Catalunya [Association of Theatre Companies of Catalonia], the first quarter of the 2022-2023 season saw an 8% increase in the number of spectators (or, in other words, 700,000 more spectators) compared to the same period in the previous season.

Audience participation ranges from meetings between audiences and artists to their involvement in theatre programming.

In parallel to this movement of cultural promotion on the part of politicians and agents in the sector, the last decade has seen a second movement calling for audience participation. Roberto Fratini, professor at the Institut del Teatre, playwright and art theorist, wonders what this wave, which is widely accepted and shared in society, is all about: “Participation has become synonymous with interactivity, with the capacity to come together, to foster a certain kind of togetherness, closeness or proximity; because participation is synonymous with socialisation, the arena for a fruitful exchange of experiences, opinions and feelings; because ‘participation’ is even a festive phenomenon”. This participatory movement has taken shape in a multitude of formats and proposals ranging, to cite a few examples, from audience-artist gatherings to audience involvement in theatre programming, the creation of spectators’ associations, the presence of non-professionals on stage or community creation shows, such as the La gata perduda community opera initiative promoted by the Liceu, which was seen last autumn with the participation of more than 350 residents in the Raval neighbourhood.

In short, in this “era of participation” in which we are immersed, audiences (or non-audiences) have become users. Or in the jargon of cultural management, there has been a shift from politics of access (so that people can go to the theatre) to access to the means of production (so that people can do things on stage). But is all this real, is it a real commitment to audiences?

1st Congress of Theatre Spectators

Last autumn, two international events of a certain scale and originality were held in Barcelona that placed the spectator and the citizen at the heart of the debate. On the one hand, a congress of theatre spectators, the aim of which was to collect the concerns, challenges and aspirations of theatre audiences. In other words, a forum on audiences, but letting them speak, without philosophers, educators, cultural managers or artists monopolising the debate. On the other hand, the second major event was Culturopolis, an international conference organised by Barcelona City Council for reflecting on and discussing cultural rights. Both events shared the same political agenda, which once again included citizens’ cultural participation, the recognition of diversity, creativity, access to cultural practices… But let’s take a closer look at this unique congress on theatre audiences.

The 1st Congress of Theatre Spectators, organised by Àfora-Focus and held at the Romea Theatre from 24 to 26 October 2022, brought together some fifty people from all over the world with the aim of rekindling collective energy in the wake of the pandemic. The curator of the congress, Pepe Zapata, began by saying that audiences are still the great unknown and a mystery that everyone wants to unravel. Apart from the conferences and workshops by performing arts experts and professionals – Zavel Castro, Roger Bernat, Antonella Broglia, Toni Jodar, Katya Johanson and Antonio Monegal – that acted as a conceptual framework, the highlight were the interventions of the audience and congress participants, organised into five debate tables, and the reading of the theatre spectators’ Barcelona Manifesto, which they drew up during the online work sessions prior to their arrival in Barcelona. All the materials are available on the Congress website.

Audience-congress participants at the 1st Congress of Theatre Spectators, held in Barcelona last autumn. Photo: Vincenzo Rigogliuso

Audience-congress participants at the 1st Congress of Theatre Spectators, held in Barcelona last autumn. Photo: Vincenzo RigogliusoThe round tables demonstrated the multiple existing forms of audience participation in the performance, while also defending the spectator who only wants to be a receiver, who buys a ticket, goes to the theatre and returns home. This audience profile (which is by far the most common) was perhaps not included in the Congress itself, in order to legitimate and acknowledge this practice and, in this way, connect with the main thrust of society.

If the contents of the experiences presented had to be summed up, it could be said that two main types of audience participation were noted: one of a more civic or political nature, and the other of an artistic nature. In both areas, there is tremendous room for growth, and the institutions should pay close attention so that all of this can keep developing. Spectators’ schools, community theatre programming committees and spectators’ associations that organise activities are some examples of practices that move in the direction of greater audience involvement in what they want to see, in education and continuous learning, and with the desire to build alliances and relationships between spectators, between equals.

There are two main types of audience participation: one of a more civic or political nature, and the other of an artistic nature. In both areas, there is tremendous room for growth.

The defence of the model of spectators’ schools, which has often been accused of being elitist, was interesting, as it appealed to the audience’s desire for self-education and self-organisation, which does not follow any political agenda. Among those present in the audience at the Romea was Laura Dulcet, from the Associació d’Espectadors de Teatre del Mercat Vell de Ripollet, who more than 25 years ago advocated for the reopening of an abandoned theatre and the civic management of the programme, in a municipality where the percentage of the municipal budget allocated to culture, per inhabitant, is the second lowest in Catalonia. This spectators’ association of this theatre, together with the association El Galliner de Manresa, linked to the Kursaal theatre, are the leading initiatives of community theatre programming in the country.

As for activities of a more artistic nature, the round tables at the Congress highlighted examples of relatively formal activities of meetings between audiences and artists, audience participation in the creative process and, finally, participation in the joint creation of shows. Roberto Sánchez Piérola, a spectator from Peru, pointed out the importance of the social element of theatre spectators over and above the artistic one. People, he said, are sometimes more eager to share what they have experienced and how they felt watching a certain show than analysing or seeing how the show has been constructed. The approach to the activities cited by this Peruvian spectator is unique, because the audience’s approach to the shows is usually very intellectual or rational, while he advocated an emotional approach, which clearly has less standing in the social sphere.

The Congress ended with the reading of the theatre spectators’ Barcelona Manifesto, which included some specific demands, but above all reflections and questions about identity, representativeness and the role of the audience: “What relationship do we want to have with the artists? What does it mean to respond to a show? As a spectator, is it interesting to meet the artist after the show? How can we make the audience play a more active role?”

What problems does the audience experience?

Beyond the studies and reports on cultural audiences, and according to Agost Producciones’ experience of more than ten years in contact with theatre audiences, we could say that spectators experience a number of problems (especially when related to contemporary artistic productions), and that this would explain the desire for participation and active involvement in the performance.

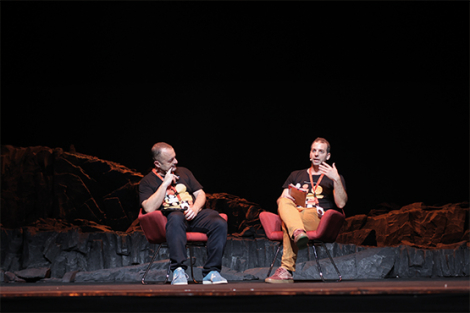

Pepe Zapata, curator of the Spectators' Congress, and Miquel Valls, coordinator. ©Vincenzo Rigogliuso

Pepe Zapata, curator of the Spectators' Congress, and Miquel Valls, coordinator. ©Vincenzo RigogliusoA few days ago, the magazine Nativa published an article by the musician Kike Bela in which he candidly stated: “As a musician and creator of shows, after performing I have never had a meaningful and critical discussion with the audience about what they have just seen” Why does this happen? How can there not be any constructive dialogue after a performance? In the case of the performing arts, one of the main audience participation activities are the post-show talks organised after the performances between the company and the audience. In most cases, the talk is poorly designed, and this brings some of these issues to the surface. Basically, what happens is that the relationship continues to be hierarchical, even though the show is already over and the work no longer belongs to the artist, but to the audience. The artist continues to occupy the heart of the conversation and what they normally do is explain the piece, how it was created, what it meant to convey... What’s more, the design is effectively restricted, because who would dare make a negative statement directly to the artist in the presence of the audience-fans? This means that the usual tone of the conversation is one of flattery towards the company, besides the fact that the spectator uses big words to demonstrate their knowledge and to be heard by the rest of the audience. Exaggerations (hardly any) aside, what is the point of all this? The Manifesto’s spectators, and it seems the artists too, asked themselves this question.

So what happens to the spectators? If we had to build a “facial composite” of today’s audiences, we would say that they are a group of individuals (basically women) who anonymously go to the theatre to watch, silently and motionless, what others (politicians, managers, artists) have thought up for them and who experience a number of problems: they don’t understand it, they don’t feel intellectual enough, they would like to do more than just sit in their seats, and they feel used (they are sought after when they are needed). Perhaps the solution lies in the initiatives mentioned at the Congress of Theatre Spectators, and in the fact that the spectator regains lost ground in the political (self-management) and creative spheres, which have been delegated to politicians-managers and artists. From passive spectators to authors of their own story.

The newsletter

Subscribe to our newsletter to keep up to date with Barcelona Metròpolis' new developments