“As an artist, I believe the true worth lies in the piece I have yet to create”

- Interview

- Jan 24

- 18 mins

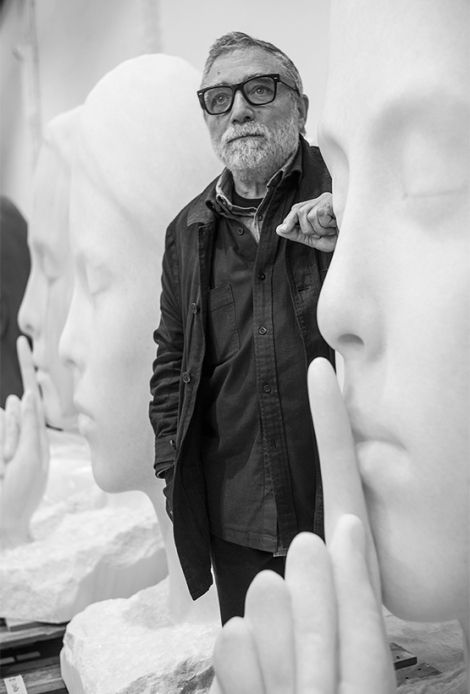

Jaume Plensa

Jaume Plensa receives us on a Friday morning in his studio. The interview unfolds in one of the workspaces, where there are various enigmatic faces of women with closed eyes, in various sizes and materials. The workspace is abuzz with activity with projects underway for China, the United States, South America and France. Throughout our conversation, a polyphony of quite grating metallic sounds serves as a musical backdrop, punctuating the artist’s measured speech. “These sounds come from various machines,” he explains. “One is used to bend the letters of a work in progress, while the other uses rivets to connect the pieces of an alphabet curtain. The heaters are also on to warm up the space because it’s starting to get very chilly in here!”

Jaume Plensa (Barcelona, 1955) is one of the most internationally renowned Catalan and Spanish artists. A sculptor, draughtsman and engraver, he studied at the Llotja - Escola d’Art i Disseny and the Reial Acadèmia Catalana de Belles Arts de Sant Jordi. Plensa began exhibiting in 1980 in Barcelona. Since then, his works can be seen worldwide, prominently featured in Europe, the United States and Asia, displayed in public spaces, private collections, museums, galleries and biennials. His accolades include the Order of Arts and Letters medal (1993), from the French Ministry of Culture; the National Prize for Plastic Arts from the Generalitat Government of Catalonia (1997); and the National Prize for Plastic Arts (2012) awarded by the Ministry of Culture, followed by the prestigious Velázquez Prize for Plastic Arts one year later.

The year 2023 has proven to be remarkably productive for you in the city, beginning with the premiere of Macbeth at the Liceu.

It’s one of the most interesting projects I’ve had the opportunity to undertake. Years ago, I collaborated with my friends in La Fura dels Baus on various set designs and costumes for opera, but I have since distanced myself from that realm. I am not a set designer, costume designer or stage director; I am an artist. On this occasion, I proposed a dialogue with Verdi’s opera, transforming an action into a public space. For me, the theatre is a public space. I brought my world to the stage, but without too much theatricality. I am very familiar with the piece.

My first sculpture featuring text, with an extract from Macbeth, was a magical moment when he realises he hasn’t just murdered a king but has killed the possibility of sleep (“Sleep no more”). Despite being a sung performance, the opera is replete with silences, in which I created almost empty spaces. I tried to give equal significance to what was happening on stage and what was happening in the auditorium. This is often overlooked but is paramount: within that auditorium, 2,400 individuals with a powerful energy; my task was to harness and reflect it back onto the stage. I have learned this from working in public spaces, and it proved successful. I think this piece will garner deeper understanding with each passing year.

How do you conceive your pieces in terms of the space they’ll occupy?

I always find the process of approaching a project complex. Being a very emotional person, I often struggle until I establish a dialogue with the environment. There are various approaches to intervening in public space. For instance, las week, I was in Atlanta at Freedom Park, where we unveiled a piece they acquired five years ago. When I saw it again, it felt like a message in a bottle that had finally washed ashore. This represents one possibility of intervention.

A few days later, I was in South Bend, at the University of Notre Dame in Indiana. There, I made a large-scale sculpture standing at 14 metres tall, intended for the entrance of the newly inaugurated museum. This piece was designed specifically for its location – it resembles a staircase connecting the sky and the earth, exuding profound spirituality. Just yesterday, the museum director sent me a photograph of the first snowfall, revealing the sculpture covered in snow. It’s exhilarating! It would never get covered in snow here, but it integrates with the space there. This is one of the most rewarding aspects of my work.

You advocate for the idea of caressing sculptures. How do you hope the audience will engage with your works?

I’ve delved deeply into public space, both as a concept and an intervention, and it offers something that’s sometimes lacking when I exhibit in galleries or museums, which is integration with the community. Works housed in a museum or gallery or acquired by a collector gain a kind of private protection, which is absent in public spaces, where they must fend for themselves and there is nothing to shield them.

A few years back, I created a small pavilion on the Japanese island of Ogijima. The project’s curator says the work is doing very well because there’s a notably long waiting list of people eager to get married there, an idea that never crossed my mind! Similarly, just as this piece has sparked that response, the Crown Fountain in Chicago has stirred children’s affection for the artwork, something I hadn’t anticipated. While it wasn’t designed with children in mind, discovering their fondness for it is fascinating. In other words, people often embrace the works in ways that wouldn’t have occurred to me.

© Enrique Marco

© Enrique MarcoCertainly, 2024 marks the 20th anniversary of the Crown Fountain. How would you describe the evolution of your sculpture over two decades?

That piece came into being in the year 2000 and was inaugurated in 2004. It was both a beginning and an end. An end because I was working in an abstract, more symbolic realm. The glass towers I created resembled large buildings where people lived, and the portraits of those individuals led me to this new figuration [he looks around, gesturing to the faces around us]. I’ve held onto this idea of portraiture by exclusively focusing on young women, as they preserve the memory and future of creation.

I decided I would never replicate a piece like the one in Chicago. Despite receiving other commissions, I turned them all down because I wanted there to be only one. I chose to leverage the lessons from the Crown Fountain but using traditional materials such as stone, bronze and wood. I documented the entire process on video. Here, I capture the person and use the distortion technique I learned back then – elongating faces to evoke a distinct sense of spirituality.

In a way, each project feeds a myriad of future possibilities, acting as a laboratory for other pieces. Yet, it’s true that the focus of my work has shifted towards specific elements; perhaps I engage less in installations now, contemplating instead a drier, more solitary and more unique creation.

And who are the women you depict?

They are individuals from diverse backgrounds because my intention is to explore globality and diversity. It’s about expressing our strength as a collective, where each person retains their individual identity, personality, cultural roots and perspectives, all while existing together. I’m particularly drawn to the notion of exchanging information within this diversity. I believe that both alphabets and faces allow me to do so.

Text is incorporated into many of your creations.

The initial pieces featuring text were inspired by specific excerpts from the poetry of authors who have long captivated me, such as Baudelaire. I have kept up this practice, still working on some drawings intertwined with his texts. I consider the poet a vital figure in society. We often overlook the fact that poets act as small souls who move and harmonise our thoughts. I value the poet as a concept; they don’t own poetry, but they harness it. Poetry is a part of our lives, something universally accessible, yet the poet possesses a unique wisdom.

I’ve always believed that words make us more human, akin to the score of our voice. This aspect strikes me as beautiful. Writing our voice is a necessity, much like a composer penning a score for someone else to interpret. Text carries an archaic element of great depth.

In some sculptures (spheres and seated bodies), you also blend letters from different alphabets with musical notes.

I am a music lover. I’ve often shared that, as a child, when I had disagreements with my brother, I would hide inside my father’s piano, which had sliding doors. That space next to the harp had the perfect dimensions for my body. The lingering scents of wood, felt, and dust have never faded from my memory. Nor have I forgotten the times my father played without knowing I was inside. Over time, I’ve come to interpret the instrument’s vibration as the pulse of life, the energy that propels us. Through the years, I have realised that music, especially its fundamental vibration element, has profoundly influenced me.

You often talk about creating beauty. What is your underlying goal of your work?

I aim to engage in a dialogue with society. While my work isn’t necessarily pedagogical, I do strive for an emotional connection with my work. I consider the pursuit of creating beauty crucial because human nature is inherently imperfect, and one of the fascinating aspects of creation is the evolution of thought. Art holds something enigmatic; it’s like a mirror in which you can see yourself.

I’m often asked why the faces recurrently have closed eyes and tranquil expressions. It is a deliberate choice to encourage each person to look inward, unveil the hidden beauty within themselves, and strive to express it. Art should help people to reflect on what they can contribute to the community.

“The pursuit of creating beauty is crucial because human nature is inherently imperfect. Art it’s like a mirror in which you can see yourself.”

And in a fast-paced society inundated with stimuli like ours, what should art offer?

The pieces made with mesh have enabled me to delve into a theme that captivates me: invisibility. In 2018, I unveiled Invisibles at the Reina Sofía Museum’s Palacio de Cristal in Madrid, featuring a collection of mesh faces. I urged visitors to partake in a visual perception exercise. We’ve grown accustomed to things being [he cracks his fingers] immediate... and at times, you have to say, “Stop and look. Wait a bit longer and look better”. That’s when you have the revelation: “Oh, but it was there, and I hadn’t noticed.” We find ourselves surrounded by almost holograms, shadows, ghosts and images that slip away from us because we look too quickly.

I remember when I created the intervention Echo in Madison Square Park in New York. Laura [his wife] and I would sit on a nearby bench to observe people’s reactions. Many of those passing by would take out their mobile phones, snap a photo and move on. They spent a few seconds in front of the piece because they already had it on their phones. I found this way of engaging with art very intriguing – there was no contemplation.

During the presentation of the Poetry of Silence exhibition at La Pedrera, you shared your aspiration to leave a legacy in the city. Some years ago, you conceptualised a large piece for the waterfront that ultimately didn’t come to fruition. Do you have any other ideas in mind?

Just like they wanted to do something with Chillida in San Sebastián, his hometown, a similar effort hasn’t been pursued here. It’s not a matter of whether I want it or not. Of course I do, but the desire must be shared by more than just myself. This question shouldn’t be directed at me alone. An artist is not a solitary figure within society. I did not decide to create the Crown Fountain, I was invited to. When you receive an invitation, you can accomplish extraordinary things, but you need support. I don’t wish to impose anything through obligation. If the invitation doesn’t come, well, that’s okay.

“When you receive an invitation, you can accomplish extraordinary things, but you need support. I don’t wish to impose anything through obligation. If the invitation doesn’t come, well, that’s okay.”

Do you feel that you receive less recognition here than abroad?

When you’re a local, everything seems more complex. There are times, especially at home, when a sense of naturalness seems to be lacking in everything; it’s really odd. Just the other day, I inaugurated exhibitions in Atlanta and Indiana, and everything was much simpler. The foreigner’s perspective is always interesting. In my youth, I spent several extended periods of time in Florence. During that time, I befriended the former director of the Tel Aviv Museum. I recall a conversation about Petrarch one day when he told me, “Jaume, conceptually, you should always strive to be a foreigner, no matter where you live.” This notion left a lasting impression on me, and I’ve tried to live by it: maintaining a certain distance with things. Otherwise, there’s a risk of becoming trapped in the local, and that is devastating. The same principle applies to romantic relationships; you can get trapped in the routine. It’s about transforming the ordinary into the extraordinary, turning the local into the unique. At times, I believe we lack this distance with our own reality.

As someone who visits many cities, how do you see Barcelona?

Culturally speaking, I feel the city has seen better periods. Nevertheless, that’s life; there are times when patience is needed, and circumstances don’t remain the same. The reality is that we live in a country where culture and education are excessively shaped and intertwined with politics. Here, a change in the city council brings about changes in cultural policies, and changes in government lead to amendments to education laws.

In November, you delivered the inaugural lecture at the Escola Massana. What advice do you give to young artists?

I’ve taught at the École nationale supérieure des Beaux-Arts in Paris and the Art Institute of Chicago, and I’ve never felt more experienced than a student; I was simply older, but we were on the same path. The advice I’ve consistently given to students is: believe in yourself. In our wonderful craft, everyone else can be wrong, except for you, and that wields extraordinary power. This is why the political world harbours a certain fear of artists. Don’t trust me or someone else, not magazines, biennials or directors; trust yourself, you are the centre. It might sound a bit strange, but this is the power of art. Each artist potentially possesses an extraordinary truth.

You have artworks scattered across the globe. Is there any specific one you would highlight?

©Enric Marco

©Enric MarcoThere are pieces I wish I could visit every morning when I get up, enjoying breakfast in their presence. For instance, there’s one called Roots in Tokyo, inspired by the concept of roots penetrating the earth and sprouting, and that one particularly moves me. Quite often, I find myself envious of my works installed in such marvellous locations.

There’s one, in Sweden, on a small island in a park called Pilane, quite difficult to get to. If you can, go see it because it stands alone for most of the year, with sporadic visitors for twenty or thirty days. It’s one of the most beautiful places I’ve been to. There’s another piece in Napa Valley, amidst vineyards, and I often reflect on the privilege it enjoys being there. My artwork has been fortunate to establish this connection with the environment. Do you remember the piece I installed with its eyes covered on Fifth Avenue in New York?

“Quite often, I find myself envious of my works installed in such marvellous locations.”

Yes, of course, Behind the Walls. What became of it?

After being there for a few months, it moved to the National Museum of Art, in Mexico City. In the end, a collector bought it and gifted it to the University of Michigan Museum of Art. Now it stands in front of the museum’s entrance in Ann Arbor. It’s a place I really like, and I find it conceptually beautiful because its eyes are covered right at the museum’s entrance; it’s an invitation to contemplate things differently. It supports my theory that, at times, vision isn’t the most effective tool for understanding, just as words don’t always articulate a feeling or ears don’t enhance our ability to listen. Sometimes, we need other parts of the body or our sensitivity. I think we often use art in such a literal way that we miss things along the way.

There are many people working in your studio. How do you navigate the creative process?

Sculpture straddles the realms of art and industry. Here, you’ll find a lot of people assisting me, but we also collaborate with external workshops. I work in a team, which I really enjoy. Initially, I create the drawings and projects on my own, which I then share with my team. They help me in the development process, seeking the best structural and engineering solutions. It’s fascinating. We are currently engaged in various projects, each presenting its unique technical demands. At the same time, I have my own personal exhibitions. Amidst all these endeavours, a fusion occurs between the team and myself, myself and the team, blurring the boundaries of where they begin and I end. It’s a way of working that brings me satisfaction. It interweaves various sensibilities into my perspective on art and life.

Besides sculpting, you also cultivate drawing and engraving.

Drawings offer me an immediacy that I don’t have in sculpture. I work on them directly; I don’t need intermediaries. The drawings often act like a perfume that precedes something that will materialise later in the form of sculpture. I have always worked in parallel with sculpture, drawing and engraving, and I used to dabble in photography and video as well. Sculpture allows me to express things that I cannot say with other languages, and vice versa. While I seldom exhibit my drawings, I am actually in the midst of preparing a series that I will show in New York next year.

And what else do you have in the works?

My work progresses at a slow pace. I can exhibit every three years in my usual galleries in New York, Paris, Stockholm and Chicago. In 2025, I have a very important exhibition in Grand Rapids, Michigan, at the Frederik Meijer Gardens & Sculpture Park, a sculpture park where I created the mural Utopia with reliefs on marble walls. In two years’ time, they plan to celebrate the park’s anniversary along with my 70th birthday! It will be a major retrospective that will later travel to Denver. I am quite apprehensive because, as an artist, I believe the true worth lies in the piece I have yet to create. Looking back makes me feel a certain way. They are asking me to map out an itinerary of my work, and [he sighs] I can’t help but feel a twinge of anxiety. Occasionally, I am asked, “Why did you choose to be an artist?” To which I consistently respond: “I didn’t choose to be an artist; it was inevitable.” This exhibition echoes the same sentiment – it’s an unavoidable destiny.

“Occasionally, I am asked, ‘Why did you choose to be an artist?’ To which I consistently respond: ‘I didn’t choose to be an artist; it was inevitable’.”

You work a great deal in the United States.

It’s a mystery because I don’t live in the United States, yet I spend extended periods of time there. I have learned a lot from the country and am fond of their ethos: if you believe in something, you act on it, regardless of other people’s opinions. This principle fosters enormous aesthetic and cultural diversity.

In Europe, we are a bit stagnant. The need for consensus hampers many initiatives. What’s more, cultural endeavours often stem from private initiatives, granting them remarkable strength. Politicians cannot be involved in everything; they should seek the collaboration of the private sector, instilling trust. In turn, the private sector should reciprocate by giving back to society some of what society has given them. Notably, several of my pieces in Barcelona are gifts: the installations at the Sant Joan de Déu Hospital, the Hospital Clínic, and the one in front of the Palau de la Música. I also believe in giving when called upon. In this regard, there’s much we could learn from the United States.

©Enrique Marco

©Enrique MarcoHow do you envision the future unfolding? Have you considered establishing a foundation, as two of the artists you admire, Miró and Tàpies, did here?

I don’t know, yes, I would like to… I adored Miró and held Tàpies in great esteem. He helped me a lot; he was a close friend. I remember one day his son said to me, “Jaume, my father wants to talk to you.” I went to his home and presented him with the finest catalogue that had been made of my work. We talked at length; it was very pleasant. Afterwards, he walked me to the door and said, “Jaume, if we don’t meet again, I wish you the best of luck,” and, shortly after, he passed away. He was a man with an extraordinary intuitive capacity, and I cherish wonderful memories with him.

I never met Miró. In my early artistic years, Miró and Calder were my idols. People say to me, “But you’re nothing like them!” They instilled in me certain attitudes, which are extremely important, and with these attitudes, I find myself pursuing something else. I have learned a great deal from them! Some artists have the capability of leaving an inevitable legacy. Of course, when you ask me this, I don’t know if I am that kind of artist. Sometimes I am not entirely certain if, after me, everything will disappear. I’d like to think that this [he opens his arms to encompass the entire studio] serves a purpose, but I’m not wholly convinced. Art creates absolute uncertainty.

How does the public’s reaction affect you?

It’s exhilarating. Julia was initially intended for a one-year installation in Plaza Colón in Madrid, and it’s now been five years due to the public’s request to keep it in place. The same has occurred with Carmela at the Palau de la Música and with Nomade in Antibes. This pattern has repeated in many places, consistently bringing me great satisfaction. Now, as one project concludes, you’re already fretting about the next: the sculpture I have yet to create is the one that excites me the most because I believe it will be the one, finally, the truly exceptional one!

And how you do handle criticism?

I don’t read the good or the bad reviews. Laura usually reads everything. I prefer not to expose myself to it because I don’t want opinions to sway me. While there are inevitably people who disagree – and they are entitled to their opinion –, I also have the right to do my own thing. So, I don’t see any issue. The real challenge hits me every morning when I step into the studio.

The newsletter

Subscribe to our newsletter to keep up to date with Barcelona Metròpolis' new developments